There’s been a lot of talk the last year or so about the use of Artificial Intelligence for Genealogy. I’ve basically taken a laissez faire wait-and-see attitude towards it. Most of the applications of AI for genealogy are designed to save you time, maybe by drafting out a biography for you or doing image creation, repair or animation.

But I’m looking for something that can help me, and help me specifically with regards to one particular task. The task I’m interested in is reading handwriting – not just any handwriting, but the handwriting in Birth, Marriage, Death and Census records from the Russian Empire.

Transkribus - AI to Read Handwriting

I was made aware by Jarrett Ross’s post on Twitter a week ago of an online program called Transkribus.

Playing around with @Transkribus today. Any other genealogists who have had a chance to use this amazing OCR software? pic.twitter.com/oT1GrHX1Qj

— Jarrett Ross (@GeneaVlogger) January 28, 2024

Transkribus describes itself as:

“an AI-powered platform for text recognition, transcription and searching of historical documents – from any place, any time, and in any language.”

You upload your handwritten document. You select one of their public models for different languages and time periods. If the public models don’t serve your needs, you can train a custom model. They supply an introductory video on Getting Started with Transkribus.

Artificial Intelligence Model Types

Reading handwriting is a difficult problem, but is something that Artificial Intelligence should one day be able to handle.

I classify AI as one of two types:

- Expert systems

- Self-training models

An expert system is one where you as a human tell a program exactly how to do every step of a process. The program does not learn anything on its own, but the result can seem to be very intelligent and be completed faster and more accurately than any human can.

A self-training model is one where you give a general AI program lots of different problems to be solved along with the answers to each problem. You let the program itself work out how best to generalize the problem and produce a solution for it.

AI can be expert systems, self-training models, or a combination of the two.

An example is a chess program. The first programs were all expert systems. All the rules were written by the programmer. In 1997, Deep Blue became the first chess program to beat the world champion who was Kasparov at the time. This program was an expert system, but with hardware that made calculations very fast.

However, self training systems can do better. In 2016, a chess program called AlphaZero was developed that was trained solely via self-play for just 9 hours. It then defeated Stockfish, which was at the time the strongest chess program, and it won with an amazing score of 28 wins, 72 draws, and zero losses.

What is Involved in Reading Handwriting?

The goal with handwriting recognition is simply to transcribe the handwriting into text. No translation is required. We are just looking to have each handwritten letter, number or symbol converted to the correct text. And with as few mistakes as possible.

There are already many good translation tools available (e.g. Google translate) so if the handwriting is in a foreign language, the transcription should correctly translate. The program to read the handwriting and create a transcript need not translate it or understand what the words mean, but it will do better if it understands the language to know that this “i” must be an “e” since there is no such word otherwise.

Obviously, this is not a job for an expert system. Nobody can effectively describe the rules they use in their head to read handwriting. So we must use a self-training model.

Generally, if you have a 100 pages of handwritten English text all written by one person and the typewritten equivalents, a good self-training AI should be able to train itself to read that particular person’s handwriting.

And if you get 20 different people to write the same text, then the AI should be able to do a good job of generalizing its model to read not just those 20 different people’s writing, but almost anybody’s, except your doctor’s. (For your doctor, you’ll still need to get your pharmacist to read it.)

Trying an English Document

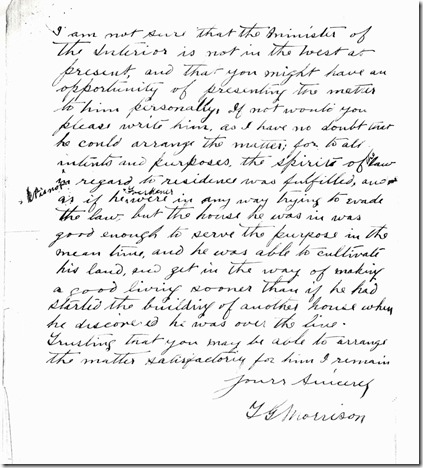

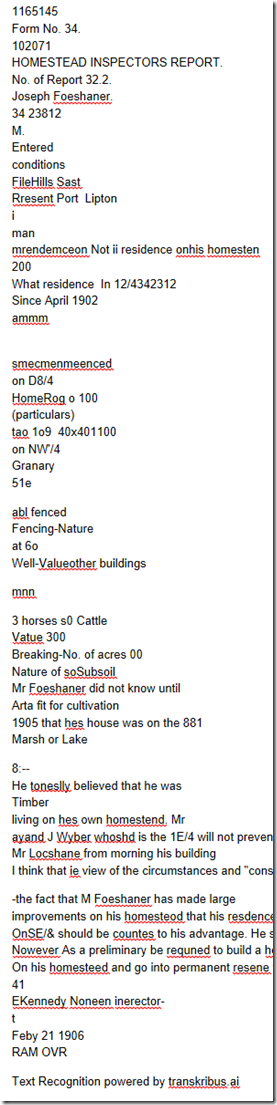

Well, let’s see how well Transkribus does. I took part of a letter from my great-grandfather’s homestead application in 1906. (Click on image to get full sized):

I selected “English Handwritten” and used it’s default AI model “The English Eagle” and in only about 30 seconds, it gave me this:

I included red underlines for Microsoft suggested incorrect spellings. I’d say Transkribus did an excellent job, and when comparing even the red underlined words, you’d have to say Transkribus did usually produce what seems to be handwritten.

It had trouble with the edits on the page, and interpreted the “it is not” inserted at an angle at the left as “Goedener”. It missed the inserted “the” in “spirit of the law” in the line before. And the most important word (my great-grandfather’s surname “Focshaner”) was inserted with a caret in “as if he ^ were in any way”, but the surname was missed and the “he were” became “herwere”.

So that’s how a page of handwritten English text can get transcribed. It did a good job on a good quality document with relatively neat handwriting. You could do as good a job yourself if you are able to read handwriting, and you could then use Transkribus to help you decide on the words that are more difficult. I am somewhat impressed.

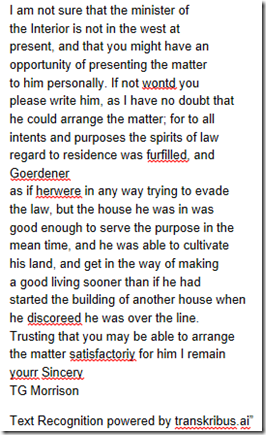

Trying an English Genealogy Document

But we’re genealogists. Our documents to interpret are not as simple as a well-written page of text. Our documents are mostly forms and we need help getting names, places, dates and notes from them.

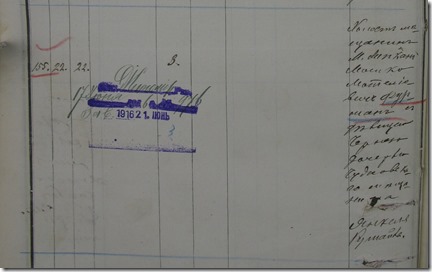

Let’s try this Homestead Inspector’s Report, also for my great-grandfather. This is more typical of one of the “good quality” documents a genealogist deals with:

The option selected again was “English Handwritten”. Supposedly only the handwriting was to be interpreted. But it gave me this:

I’ll let you compare for yourself, but I was quite disappointed with these results. They are just a bit too far away from correct to be useful.

Transkribus may have other English models that might do a better job, or you can train one yourself. I think this result reflects my current impression of how much further AI has to go with regards to reading handwriting. But it’s a start.

I don’t need a program to read English handwriting for me. For the few documents I have, I am able to do it quite well myself because I understand English and know how to handwrite in English and read English handwriting.

Any Chance At All for Russian?

All 9 of my and my wife’s grandparents (the extra is my father’s stepfather) came to Canada in the early 1900’s, two from Romania, and seven from what was the Russian Empire and now is Ukraine. All of their birth documents and their ancestors and family documents are written in Romanian or Russian.

:Let me concentrate on the Russian documents. These are all from 1910 or earlier and mostly include Birth, Marriage, Death and Revision List (i.e. Census) records and all the text is handwritten onto forms. Just over 2 years ago, I took a wonderful Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy (SLIG) Course on Researching Russian Genealogy Records, which made me do the valuable task of learning the Russian alphabet as a prerequisite.

Theoretically even though the alphabet is Cyrillic rather than Latin characters, an AI program trained on these documents should do just as well converting handwriting to text whether in Russian or in English. The quality of the handwriting would be the biggest consideration in any language.

Melanie McComb pointed me to an article that lists 3 public AI models for Russian Handwriting that could be used with Transkribus. The one called “Russian Handwriting Early 20th Century” seems most appropriate for my documents since the Russian alphabet had extra letters and the language was somewhat more complex before the Russian Revolution.

Well lets go all in and try it.

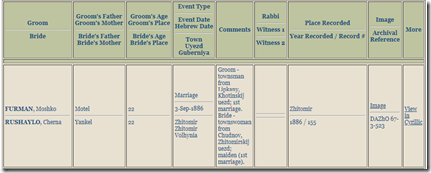

Here, for example, from JewishGen is the marriage record of my wife’s great-grandparents Moshko Furman and Charna Rushaylo in Zhitomir in 1886.

To be honest, I don’t give the AI much hope.

Even so, I go over to the Russian Handwriting early 20th century model page, and I upload my document.

Well it did give me something, actually more than I expected. And when I throw this into Google Translate, I get:

Unfortunately, there isn’t much in the translation that’s recognizable.

The names of the bride and groom that are at the left of the record weren’t even interpreted, probably because they were heavily underlined in ink, something done a lot in Russian records. Those may have obscured the names from Transkribus.

Also, old Russian handwriting tended to split words in two at the end of a line without a hyphen or any indication that the word is split. That really does a number on Google Translate’s results.

Here’s how JewishGen indexes the record:

If I take the text of the comments:

Groom - townsman from Lipkany, Khotinskij uezd; 1st marriage. Bride - townswoman from Chudnov, Zhitomirskij uezd; maiden (1st marriage).

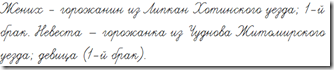

and I use Google Translate to convert it to Russian:

Жених – горожанин из Липкан Хотинского уезда; 1-й

брак. Невеста — горожанка из Чуднова Житомирского уезда; девица (1-й брак).

And then I change the Russian type font to a Russian handwriting font:

And then I throw that text back into the Russian model of Transkript, I get … unfortunately this:

I’m very surprised. That’s just about the best-written Russian handwriting you’ll ever find. I tried it on the other Russian models on it as well, and no-go.

Conclusion

It’s going to be a while yet before any AI tools will be able to interpret handwritten genealogy documents for us, especially those from before the 19th century in the Cyrillic alphabet.

For now, we’ll have to continue to rely on our foreign-language researchers who have spent years reading those documents, and can use their experience to understand them and to even find them for us in the first place.

Eventually, an AI model might be able to be trained for a particular type of document, such as the Russian marriage document I tried above. But it will take someone with the expertise, time and patience to do it.

Followup March 3:

I had two suggestions on Twitter with regards to this article:

- Try Ocelus by Teklia.

It can accept Russian handwriting and output the corresponding Russian letters. But for my test documents, when the output is copied to Google translate, not enough words are correct to be of use. - Try Yandex by Iron Hive, a Serbian company. This is a set of tools designed to help with Russian documents. There is a Yandex Vision OCR tool that includes support for Russian and English handwriting recognition. But this seems to be a paid service for programmers and I don’t see a simple way to try it with an uploaded document.

Joined: Tue, 11 Jun 2019

5 blog comments, 0 forum posts

Posted: Tue, 27 Feb 2024

Louis,

Thanks for the update and review of the latest Artificial Intelligence with handwriting. We are all hoping and amazed how fast this technology is improving.

Paul Baltzer

Joined: Tue, 27 Feb 2024

2 blog comments, 0 forum posts

Posted: Fri, 1 Mar 2024

Greetings Louis.

In a pre-AI world of web-based, transcribed, census records, successful transcriptions were governed by what I believe were four main factors.

1. Census Enumeration Accuracy;

2. Census Enumerator’s Penmanship;

3. Digitization Scan Quality; and

4. Transcriber’s Interpretation.

I anticipate that factor nos. 3 and 4 will be transformed by evolving AI methods. However, we will be stuck with factors nos. 1 and 2, regardless how “smart” AI becomes. What we will gain, is an improvement over human transcriptions. I am painfully aware of those transcriptions made by individuals who are completely unaware of ethnic naming etymology and who unknowingly misinterpret hand writing that is easily interpreted by someone with even the most basic knowledge of those type of names.

When we consider AI based translations, we may even have to limit the “smartness” of the AI. For instance a name like “Ivan Chorney” might be translated to “John Black” which is paradoxically both correct and incorrect at the same time. Other challenges will be met when the AI transcription process encounters linguistically abandoned words or abandoned letters in an alphabet. I also am unsure how AI will deal with periodic, haphazardly used diacritical marks by the original document authour.

What I do see in the future of AI transcription and translation, is the need to re-digitize some records that were made before the last couple of decades. Some examples of digitized government records I’ve used, reminds me a staring at clouds as a child and trying to guess what animal shape a cloud is. The “techno-geeks’ driving the AI process are definitely going to have use sizable panels of highly experienced users of those records chosen for AI analysis. Reliance on only one or university professors as “experts” may result in an AI interpretation that unfortunately will be widely viewed as “a good place to start from.”

BTW thanks for your blog post which made me contemplate this topic

Joined: Tue, 27 Feb 2024

2 blog comments, 0 forum posts

Posted: Sun, 3 Mar 2024

Typo from my last comment. Sentence should read:

“Reliance on only one or two university professors … “

Joined: Sun, 9 Mar 2003

291 blog comments, 245 forum posts

Posted: Sun, 3 Mar 2024

Hi Dave,

Yes, you have outlined several of the challenges that AI will have interpreting handwriting.

These are all likely one-day solvable, for example with regards to your point on penmanship, an algorithm may have to be trained on the writings of individual people first before it can be generalized.

And AI interpreting documents such as Russian marriage records will need to understand the basic layout and the type of phrases that are included in order to pick out the names and places and not translate those.

It will require a researcher who works with those documents to work with the AI experts and we may get something.